As of today, April 19th, my book has been in the world for three hundred and sixty-five days. Both a blip and an eternity. Book publishing years are like dog years, except the exchange is even less forgiving. One year may make you a toddler in human time; in book time, it makes you ancient. The day it enters the world, the thing is fully grown.

Here’s what I say when people ask what it feels like to publish a book: You’re in a tunnel. Pitch dark. There’s a broken faucet dripping water somewhere. The droplets echo, which is your first clue that the space around you is cavernous. (It might be a sewer? Unclear.) Somebody hands you a flashlight. The flashlight is faulty. You can click it on, but it only illuminates a short distance in front of you—just enough to shuffle a few steps in the direction you hope is forward—before it flickers back into darkness. These are the units that mark your progress: Click, shuffle, darkness. You bump into the infrequent corner, stumble on the odd dead thing. If you’re lucky, as I have been, you have a person (or many people—friends and partners and agents and editors) shuffling along with you, some of who’ve even been here before. They narrate the parts of the process they’re familiar with; say things both reassuring and alarming like big step and jump now and uh-oh. There isn’t a light at the end of it, not really. The thrill (and the terror) is in how both dimension and direction only become clear in the doing, a few steps at a time, none of which you can quite envision when you first set out.

A year later, I am still in the tunnel. I am glad to be here. I can see so much more of it now than I could twelve months ago. I can report on what it’s like to other people who consider coming in; if I’m feeling perverse, I can even tell them to join me. Perhaps most telling of all, I’ve chosen to stay here. The book—and my career as a writer beyond it—is a thing I continue to think about, talk about, commit to, promote, and protect. I didn’t take any of the emergency exits. Even when I really wanted to.

In so many ways, it’s been a wonderful year. Launching the book was a joyful time, full of promise and possibility, in the way things are when they’re still dewy with the present tense. The book was excerpted in Time (on how culture reads Black writers badly), Literary Hub (spicy, perennially relevant essay on racism in publishing), and The Walrus (an essay, also pretty spicy, on why Canadian nationalism sucks, published in a magazine that’s historically been a vehicle for some of that nationalism’s core myths, by an editor friend with a great sense of humor). The collection received generous praise from writers I admire. I am deeply proud of the way readers have engaged with the book; how they said it gave them a way to express something that felt true but that they’ve never had the words to articulate, which is, to the letter, exactly what I sat down to accomplish. I am grateful to have cleared space in my head for the next project by getting these thoughts down on paper and I am still a little stunned that I was lucky enough to find people who wanted to make those thoughts public.

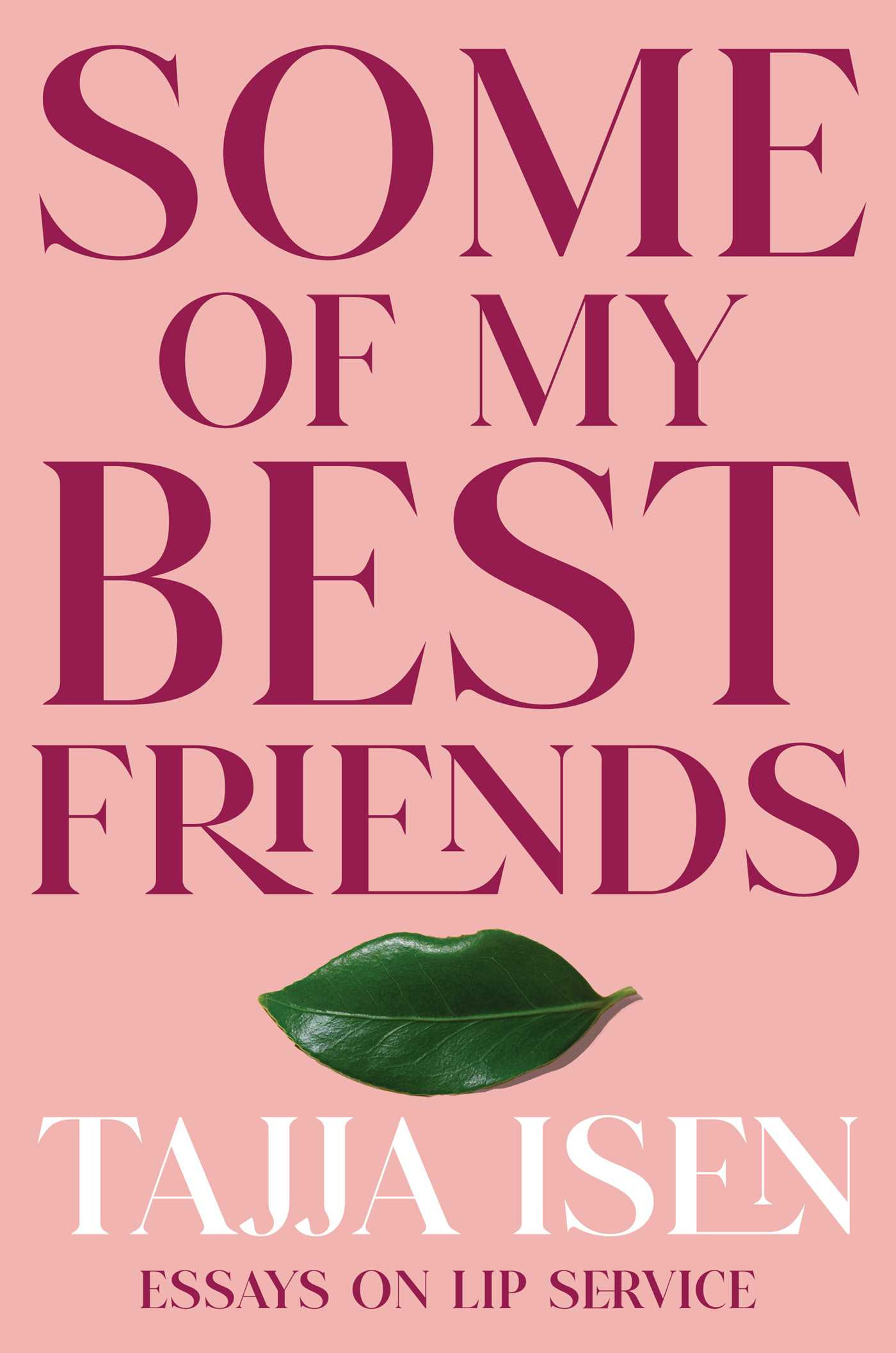

But I have also struggled a lot this year. With the way people talk to me about the book; with the vocabulary and the reactions and the affects that it summons, many of which are separate from the contents of the book itself and more a reaction to the idea of it. The book is an essay collection about the absurdity of living in a world that speaks the language of social justice without acting on that speech, and my own lived experience of that absurdity. I knew, when I wrote it, that it was subject matter that could potentially, uh, alienate some people.

At my book launch last year, in conversation at The Strand with the incredible Jamia Wilson, I described Some of My Best Friends as “a book that’s constantly looking over its shoulder.” What I meant by that is that it’s a book that tries to sidestep its own uncharitable reading; to offer in its pages a manual—or at least a very strong suggestion—about how, and how not, to approach it. (See the descriptions of the above excerpts.) Our cultural talking points for books that touch in some way on race and social justice are rather tired. They tends to cluster around how harrowing it is to be “a minority”; a zoological approach that neglects the fun stuff, like craft and style and humor, and the basic-human-rights stuff, like whether you think the author has a brain. It’s a manner in which you wouldn’t dare talk about, say, a Joan Didion collection. In response, my book tries to build its own vocabulary for how to talk about race and social justice—a way that’s sly, funny, sharp, and ultimately makes clear that it is not a book about identity, or suffering, or—especially not—about “what it’s like” to be a person of color.

As it turns out, it sometimes got read that way anyway! As I kind of knew it would when I set out, and I still wrote it. In some ways, it’s a delicious irony—the book is literally about slapping vaguely feel-good language on something as a way to avoid substantive engagement with it—but sometimes it hurt and got me really in my head. I agonized over the decision to include the phrase “about race” in the cover copy, but ultimately decided to go with it for clarity and concision. (One day I will write an essay about the phrase about race and what it actually means when it gets appended to works of art; how it’s not a descriptor but a value judgment. The Work of Art In the Age of Diversity Talk. If you want to commission this essay, hit me up. I tried to write a pitch for it a year or so ago, as a promotional essay keyed to run around the time the book was published, but I was too angry to do it well.) I’m still not sure if this phrase set people up to expect a different book from the one that they got—one that participated in the discourse about race in the right way, the expected way, and therefore the acceptable way.

So, more of this year than expected has been spent defending my book from the evil-twin versions of it that exist in people’s minds. But I regret nothing. If I’d never written this book I wouldn’t have room in my brain for the next one. Nor would I have learned the rough blueprint of the tunnel, which is a gift in itself and one to be passed on and shared with other writers. If I can be part of somebody else’s ragtag party, clicking and shuffling along every few feet in the darkness, then it was worth it. I believe wholeheartedly in the separation of art and commerce—when I’m writing, I’m not thinking ok boys, how is this gonna sell—but it’s a blessing to be able to step back and reflect, even crudely, on how my creative decisions might hypothetically play in the marketplace. How, if I had to turn it into a soundbite—because you will always, always be asked to turn it into a soundbite—whether that demand is something I’d be comfortable with. If I had to appoint myself the de facto expert on the subject of my book for an op-ed or an interview, is that something I would be up for, or would it make me want to primal scream? I’m not saying that any of these considerations should hold you back from making a project the most authentic version of itself. But me, I have the kind of mind where I need to anticipate potential threats and objections. Not so I can head them off, necessarily—just so I’m ready when they come. At least nobody can say they ever caught me unawares.

And, hey, if you feel like celebrating this anniversary with me, it would mean the world if you’d consider buying a copy of the essay collection that several outlets named a Best Book of the Year; that Kristen Arnett called “wildly funny and whip smart”; and Heather O’Neill called “beautifully written and so intelligent.” It would also only help my case if you left it a review on Goodreads or Amazon. If I’m very very lucky, I will get to keep doing this.